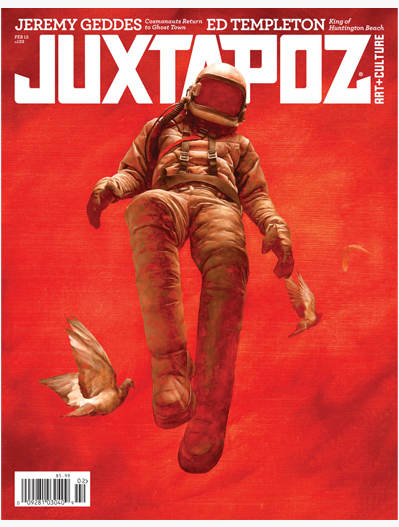

In Australia, Melbourne is known as the more sombre of its large cities. Its rain swept streets often feel a little bleak, but not usually as desolate as Jeremy Geddes imagines them. He uses his hometown as a backdrop, its streets and architecture recur throughout his paintings, but it’s a city stripped of life and noise. When his figures aren’t suspended in an empty netherworld, they haunt this quiet ghost town. It’s a world that in his most recent works has begun to crumble and break apart under a perverse distortion of the usual Newtonian Laws.

Jeremy’s paintings are painstakingly detailed. He captures subtle shifts in light and shadow and builds complex forms from deft brush strokes and subtle glazing. He has an eye that is careful, precise and true; it is this detail that makes the unreal feel real. His vision is not an approximation, but simply a reassembly of the world with different rules.

Jeremy Geddes sat down with friend and fellow Australian painter Ashley Wood to talk about their upcoming show at Jonathan Levine Gallery, how they work and their thoughts on painting.

A – Less than a year out from our joint show, what’s your feeling on it?

J – Yeah, I think a mix of anticipation and stress. I’ll have a good chunk of work finished for it, but I always feel like I could use another year or two.

The Beijing gig was what, a bit over a year ago, and I’ve been working solidly on paintings for this coming show since before then. The earliest painting that will be there is ‘The Street’ and from memory I’d initially planned to have that in Hong Kong in 2009. I ditched that idea when progress began to really slow down. It was the asphalt that did it! It wasn’t something I’d ever tried to paint before – always a danger with deadlines. I think I must have repainted it 2 or 3 times by the end. It had a randomised quality that was anathema to my painting style, which made it quite a trick.

My paintings take a long time, but on the positive side it means that there should be a nice evolution in my brush marks on display. I think I’ve come along a bit in how I lay down paint in the last few years. I’ve really been pushing myself in that direction, so it ought to be nice to step back and see the progression.

Last time we talked, it seemed like you were well into your work for the show. How’s it holding up at your end?

A – You know it’s hard to tell, I have a bunch of paintings on the go, some I have a really succinct idea of where they are heading, and then there are the paintings that have a mind of their own. I guess I’m ok, just need to keep at it. Painting isn’t a simple or easy process for me, takes much time to get it right.

J – I love the way you work like that, in the flesh you can really see the history in your paintings, each idea you try leaves its mark on the later layers of paint, a build-up of multiple palimpsests that all inform the final painting.

My work is totally different in that way, if I change my mind on a section of the painting I will have to fight the underlying texture. It’s one of the reasons that I paint primarily on board, so I can get a palette knife in there and scrape away the failed idea. It’s also why I’ve developed a technique to try and minimise that kind of rework.

Like you, it can take me a long while to find that right path through a painting. It’s not always obvious what elements are needed and what are not, it’s like intellectual sculpture, just chipping away at those ideas and elements that aren’t necessary and finding the underlying form. It can take a long time to get there, and I’d rather do that work (and rework) on small preliminary paintings than stick myself with weeks or months of rework on the large painting. If I try to rush that initial stage too quickly I usually end up paying for it in the final painting. In ‘A Perfect Vacuum’ I ended up repainting the figure three times because I launched into it too quickly. But with your work, that build up almost feels like an integral part of the final painting.

A – I agree with that, I become quite attached to the ghost images that flutter just beneath the final image; I like the viewer to be able to see said journey and process. You’re right about doing the prelims though, even though I mostly sidestep it, it really does help distil the idea… I guess I’m a sucker for the struggle, and many times I hamper my own progress or mess with my system to see what happens.

J -What’s great is that although we approach painting so differently, our work still hangs really well together. We have a similar aesthetic sensibility and we approach our work from similar places and I think we both love the nature of paint itself. Our work is in some way cohesive, but the end result is different enough that you’d never confuse them when they’re staring at you from a wall.

A – Yep, our work does sit well together, which on the surface would seem odd, as our swagger and technique are very different. But as you say, we come from similar aesthetic places; just the birthing aspect subverts us into what we are.

J – I’d say that in some ways, the preliminary paintings I do can have similarities in style to your work, although they’re obviously not as proficient. I’m in a very different headspace when I’m working on them, perhaps a little less self conscious, I’m looking at problems and trying to fix them rather produce a finished painting

A – Yeah, as we have chattered about before regarding prelims, I enjoy yours as much as the final painting. Take the prelim for ‘Heat Death’, it has a feeling about it that just really makes me lose myself in it, the details are scant but that makes me involve myself in it more on an emotional level. It’s hard to quantify…

J – Yeah, it’s the beats of tone and colour in the image that I really strive to nail when I’m doing those loose studies, so it’s great to hear that they’re present and singing together.

I find that when I’m focused in on the detail of the final painting and working to get the form of a particular element feeling correct, it can become disconnected from the painting as a whole. Very often, when I finish the detail pass across the whole painting; the elements, whilst working individually, will feel atomised and distinct from each other. For me, this is when having the study sitting next to the large painting can be really useful, it’s like the solution to the other piece of the puzzle. I can look at the painting and go, right, that bit isn’t gelling, why? And then I can look at the study and go, ah right, that has a warm glow, or is pushed further into the background with haze or whatever it is, and get to glazing in the subtle shifts and nuances of tone that have gotten lost in the myopic process of detail painting. Even when the final painting changes significantly, like in cluster, where I’ve significantly added and changed elements from the preliminary study, I still have that emotional key in the loose painting that I can refer to.

I am a detail junky though, I really want the painting to work at any distance, from 10 meters to 10 cm, and to reward the viewer with different things. My goal is always to fuse those two elements into a whole that is greater than the sum of either of its parts. It’s always a tension, and something I think I’m becoming better at the longer I work at it.

A – You know it’s funny, I can’t normally stand detail or realism in painting, very redundant in most cases in my world, but you make it work. It comes down to what you were just saying, the detail doesn’t dictate the image, it allows the primary experience of the image to shine through, the idea, and if you so desire you can get up close and check the manic detail. Beyond a deft technique to create your work, I’m more into the ideas and imagery I see, yeah, your paint skills are cool, but the ideas are better, the silent mystery of the astronaut exploring tattered ruins of modern culture, to twisted human forms, they’re a much bigger lure for me. If it was just you doing chrome parts of cars and funky reflections, well shit, I would punch you in the nuts, regardless of how well and detailed you did it.

J – Ha! I know where you’re coming from, although for me, I have to respect the work and achievement. Painting well is always hard, hats off to anyone who can manage it. But it’s just not the kind of work that would get me up in the mornings.

A – Here’s a question, take a painting that looks naive, kinda crap but has a great idea behind it, yet if one was to see the image without said idea being told via words or audio to coincide with the viewing; is it just a naive, kinda crap painting?

J –I think that without the right tools, the idea can’t be expressed adequately. You might see a glimmer of what might have made a great painting, but without the painter putting in the effort to resolve the problems inherent in an image, I think you can really only say, “well that could have been a fantastic painting”. I’m not saying that I do a great job at this, it really is fucking hard, but yeah, for me there’s a minimum level of competency that has to be there before I can engage.

Also, as a survivor of the world of bullshit art school wank, I’m very suspicious of ideas expressed in an impoverished fashion. I tend to think that if the technique is off, probably everything behind the painting is of a similar quality. I find that thinking through the technicalities of image making also helps me refine the ideas behind the painting. The ideas inform the technique and the technique informs the ideas.

I do think that technique always and only exists to service the idea though. My goal in improving and expanding my actual craft of painting has always been to give myself the tools I need to paint anything I want. I hate the idea of having images in my head that can’t be adequately translated onto the board. If I didn’t have a huge backlog of images waiting for me to get good enough to paint them I’m not sure the whole thing would be worth the effort.

What do you think? I seem to remember a few times you’ve been pretty harsh about work in the past!

A – Well yeah I’m harsher, I think visual art primarily based on theory and conceit is shit, I have no time for it, but that’s me. I believe the intellectual theory idea over image is a backdoor for basically untalented bullshitters to play at being an artist. But their shit is needed to keep the art machine going; many galleries have to fill their walls with something I guess.

J – Yeah, I really try to keep my head out of most of that. I see myself as being in the business of picture making, trying to construct very particular images that can get stuck in people’s heads and bounce around.

Beyond that, I’m not sure I see myself as connected to the “art world”. I don’t go to galleries much, don’t go and have coffee with fellow “artists”. I’m just in my studio, trying to get better at this very specific craft.

“Conceptual artists” might as well be plumbers for all the connection they have to what I’m trying to do.

For me it’s all about trying to make that great image, that perfect painting …

A – A well executed painting will always resonate, a well executed painting with a great idea that spills fourth will pummel ya head with happy hormones. A shit painting is just that, shit.

J – Yeah, I pretty much agree with that. The tendency to accompany the work with an essay outlining the themes and meaning is, to me, just announcing to the world that the paintings have failed. I really think the image should be self contained; all that you want to say about a painting should be within the painting. You may want to say a lot, or be ambiguous, but if you can’t pull that off within the four walls of the image, you need to try harder.

It’s an interesting question though, how much information or how much of an idea can be reliably conveyed within a particular painting? It’s something that I’ve thought about a lot as my paintings have evolved. It’s been my experience that if you load up a painting with a very specific narrative and meaning, it’s very unlikely that the viewer will unpack that information in the way you expected. They will usually focus on a few small elements and create a narrative that resonates with them, and then selectively focus on those elements which fit with their already conceived idea.

It was a frustrating realisation at the time; that there is a finite amount you can communicate with an image. You can do it to greater effect in illustration, or in – for example – religious painting, but only because you are referencing imagery or narratives from elsewhere. But when it’s just a pure single image, there are real limitations to accurate and specific communication.

The more I thought about it however, the more I realised that this is a strength of painting as well. It may be an obvious point but it took me a while to work out. You can set up questions and then never supply any concrete resolution, which I think means you’re free to ask really interesting questions. It’s not a frame of a film, there’s no next moment, all you get is that one image. I love that about painting. You’re not let down by a shitty ending because everyone makes their own ending, one that resonates for them.

A – I like that “not let down by a shitty ending”… hopefully…

J – Yeah. All you can do is your best. Failure is always hanging there but it’s a good motivator. I find, I’m constantly stressing that one part or another of a painting is going to fail. And if I feel like a section has, that part leaps out at me from the final painting, haunting my perception of it. It really drives you to get your paintings right; or at least as good you can make them.

A – So I guess with under a year for what is easily our biggest showing, I think we should start working on the essays to accompany the artwork then!

J- Ha!

A – Seems like yesterday we started chatting via email, though it’s been many years, I never thought our paths would lead to a show in NYC together, but I’m damn happy it did, and shit, we did it without an Australian art grant.. Good Lord!

J- Forward to the show!

It appears your interest and inclination toward painting started at a young age. How did you get started in painting.

Painting happened as a natural progression from drawing, which I had been doing from a very early age. I honestly can’t remember when I began; it has just always been a central element in my life.

Realism was not really prominent when you went to art school. Were you a bit of an anomaly there and did you have to be strong in maintaining you interest in realism. How much did you have to be self taught at painting.

Although I went to art school for five years I pretty much regard myself as self taught. As you say, the techniques involved in realism had been dropped from the syllabus in the sixties. This meant that many of the lecturers now staffing art schools (in Australia at least) hadn’t been trained in realism, and therefore weren’t in a place to teach it.

But I don’t necessarily think that a lack of formal training in realist technique is a bad thing. I spent quite a lot of time both during and after art school reinventing the wheel. It forced me to solve problems and approach issues in a different way and therefore possibly achieve results that are somewhat unique. The down side is that it takes a lot longer to get there.

I understand you sometimes paint 12 hours a day for weeks. Do you need or have strategies to sustain interest, enthusiasm, concentration.

I think it’s crucial to love what you are doing if it needs that kind of time investment. You obviously need to be invested and interested in the final product, but I’m not sure that a desire to make a good painting alone would be enough to hold me for the months of 12 hour days it takes to produce a piece.

You really need to enjoy the day to day mechanical aspect of painting as well. The paintings I make constantly present me with endless little problems to solve as I progress, (how should the glass be shattering if force is being applied this way, how should these shadows be falling on this object, what type of brush marks will best describe this form etc.) It’s these minor challenges that keep a painting dynamic to work on, and interesting to come back to day after day. I love solving these issues, I love becoming lost in the dimensional qualities of the work, and feeling my brain slowly resolve issues I previously thought were unfixable. It’s an amazing job to have.

Given it can take so long to complete a painting, what is the process you use to conceptualize a piece, refine it, “test” it, etc. so you do not get part way through a painting and discover, “this is not working”

Yeah, ‘this is not working’ is a terrible realisation to have 3 months into a painting.

I try to minimize it by having a very thorough preparation phase, which can easily take up to a year to resolve before I actually begin work on any specific painting. It begins with small thumbnail sketches to rough out the very initial ideas, which then evolve into small studies. I try to live with these studies for a month or two before I make any real decisions about them, as that initial excitement can be misleading. (You can all too easily launch into a work in the flush of enthusiasm without having resolved the outstanding issues and it can lead to disaster down the road.)

At some point, usually after a progression of studies, if I find that the image is still grabbing my interest I will make sure I’ve collected what reference I will need and I then launch into the big piece.

I understand you utilize music to help you identify, refine, etc. emotional feelings/elements in your paintings. What kind of music do you use and how would you use it. Are there specific pieces of music that correspond with specific paintings?

Yes, I use music extensively in this way. If I can find a piece that triggers the right emotional note, I can use that as a through-line whilst I am constructing the ideas and composition of the painting. It becomes relatively easily to test any element in the work against this emotional tone, it will either resonate with the music or it will feel off, and so it can be a great way to winnow potential concepts. The music I use for this generally ranges from modern classical to ambient and drone.

Many of my works are partially named after pieces of music that helped me resolve the emotional components of that piece, some examples are Acedia, which is named after a Sinke Dûs piece. Or the Misere/re series, which was partially named after compositions by Henryk Górecki. Obviously the names need to have more resonance than just this, but when the music, the painting and the name click, I tend to run with it.

One element of your painting that effects me greatly is your use of light. How do you create that play of light in your mind.

Thankyou. I’m constantly concerned about light in my paintings. It sets mood and tone as well as acting as the visual glue for holding disparate elements together. If you are trying to convince the viewer that the scene you are painting has a unity, understanding how light behaves is crucial. Obviously you never paint light per se, you paint the behaviour of light on surfaces and forms, and achieving cohesion in this is something I strive for.

The good thing about making a painting is that the interaction of light is always up for tweaking. There is a visual tolerance that the brain allows before an element begins to feel ‘off’ in a piece. This allows for some interesting manipulation as I can play with elements in the work, pushing their interaction with light to achieve an effect, but pulling back before I begin to undermine the sense of reality. It is a delicate balance, and something I am constantly concerned with maintaining whilst I am painting.

I also borrow from photography where I feel it is appropriate. The way light behaves in a photograph has become so embedded in our visual language and has become so integral to our understanding of images that I think it’s crazy for a painter to not pull from it when it can help achieve a desired effect.

When viewing your paintings on the internet, they have the impression of being very large paintings, yet they are in fact relatively small. How do you decide on the size of the painting.

The size I decide on can come down to something as mundane as the way I make paint marks, the action of my wrist and the way I sit or stand at a painting.

However I am also always thinking about how the work will be perceived in the flesh, how close people will stand, how much do I want the abstraction that occurs at the level of the individual brush strokes to be seen etc. This is a part of my work that I feel is still in flux and is something I intend to experiment with.

What do you think is most misunderstood about your work.

That’s an interesting question. Perhaps it is that there is no resolution to the content of the images. There is no set ‘reason’ why the scene I have painted is taking place, and consequently there is no easy way to contextualise it. I am interested in creating the work and then saying no more about it. Everything I have to say is put down in the paint. I am not giving an answer to the painting; once it is done I have no more to reveal about it.

I was having a conversation about Kafka recently, and the frustration of students who want an easy conceptual out for his stories, to categorise them in some way (they are about alienation, or identity or some other easy catchphrase). It allows people to feel that they have understood them, resolved them and therefore they can be intellectually put away into a box. But the point was that Kafka was creating narratives with no easily resolved message, they existed on their own terms, and therefore worked at the mind of the reader, unresolved, unsettled and reflecting the readers thoughts back at them.

I would like my paintings to function to some degree in the same way, although how successful I am I’m not sure.

I understand you are an avid gamer, do you think this influences your work.

No, not really. They are two extremely different art forms and the concerns of one do not easily translate to the other. The two mediums are fascinating to view in relation to each other though. One is extremely old, the basic technologies haven’t changed in generations, and so, as a painter, you have this huge library of previous paintings stretching back hundreds of years, pretty much everything you can think of doing has been done to some extent multiple times before. Perhaps you can carve out a small niche that hasn’t been fully explored, but still you are constantly aware of the weight of art history, it is both inspiring and intimidating.

Games on the other hand are an extremely new art form. The technology is rapidly evolving and so the potential branches a game developer can take are always expanding. There are so many new places to be explored in games, and the medium is constantly carving out new landscapes for itself and pushing back the boundaries of what constitute its domain. This will be looked back on in future generations as the golden age of game development, and so it’s an exciting field to both be in, or view from the outside.

What advice would you have for young people seriously pursuing painting as a profession.

Work. Love the medium, love the day to day grind as you hone your skills. Try to get as clear an idea as you can of where you want to head, identify painters that you want to be like as this will give some idea of how to move forward. Your aspirations will change as you mature as a painter, but it crucial to get some idea of where you want to end up so you can start travelling.

Who/what were your early influences in the art world? Would I be wrong in suggesting that there is some Salvador Dalí influence in your work? Is there a contemporary artist that inspires you? Who?

My early influences were mostly painters working in the illustration field, like John Harris and Chris Foss, dealing with science fiction settings which emphasised enormous scale. Among the surrealists I am more drawn to Magritte than Dali, his paintings seem to me to be the realization of a single idea, whereas Dali’s can be a bit too esoteric and random for me. These days I am mostly drawn to painters from the 19th century such as Jean-Leon Gerome and Leon Bonnat and modern realist painters like Antonio Garcia Lopez.

Are you formally trained or self taught? What is your preferred medium?

I’m essentially self taught, I went through art school, but didn’t receive any painting training whilst there. Those skills have been lost in many schools over the last century. There is a revival of a more formal training happening in some places now, but I wasn’t fortunate enough to receive myself.

I paint in oils, and have never tried any other medium enough to know if I would be comfortable with it. There is huge time investment to understand the nature of new materials before you can use them well, so without a good reason to, I don’t have any plans to move across to something else.

Would you consider yourself a hyper realist painter? I know a couple of guys who are totally insulted by that categorization. Your work could almost be called hyper-surrealism, I guess?

I’m not sure. Personally I don’t subscribe to any category, most have a semi-formal list of style delineations and goals, none of which I am interested in, I just do my own paintings, they are fairly inward focused and I don’t tend to pay much attention to the movements going on around me.

I don’t quite see the distinction between hyperrealism and photorealism, the Pop Art off-shoot from the 60’s. If it is like that, then I don’t consider my work to be analogous. Photorealists tend to produce very flat paintings, where the physical nature of the medium is hidden, brush marks blended away.

Much of what interests me in painting is using the abstract marks made by a brush to describe forms. It happens at a fairly small scale, and so it’s not apparent when the work is shrunk for print or the web, but it’s what keeps me excited about painting. In this way – at a technical level – I am much more drawn to the Victorian Academic painters and the Pre-Raphaelites.

You must have hundreds of concepts that never see the light of day. How do you distill the ideas for a single piece or a series?

I am a very slow painter, so yeah, when I get to a new work I have a lot of options about where to go. I try to make that decision by producing small studies of potential pieces whilst I am working on something else. I refine these, adding or subtracting elements, playing around with tone colour and composition until I find something that sticks with me personally, that I am drawn back to again and again. Hopefully, if all goes well, once I have finished a painting I have one particular study that has risen to the top and is the obvious next work. That’s the plan anyhow; it doesn’t always go that smoothly.

Some of your work elicits memories of reading some works of Kurt Vonnegut, Philip K. Dick, or Anthony Burgess. There a slight disastrous, dystopian type feeling to many of your paintings. Do you like to attach context to your work or leave it open for interpretation?

I leave that open for interpretation. I try to make relatively quiet paintings. Even when there is movement, like a piece of wall breaking apart, I still try to imbue the work with a sense of stillness. This is, at the end of the day, more of a product of the kind of sensations I am drawn to than an overall theme I am consciously trying to impart.

I see my work as visual representation of mental states than literal descriptions of a physical reality, although I love hearing people’s readings of the works.

Is your art an exploration of the relationship between the natural world, the world of science, and the spiritual world?

That is definitely in there, yes. Not completely intentionally, I can see a legitimate reading of them from that angle. The cosmonaut paintings I think could be seen as religious paintings stripped of their spiritual connotations, with artefacts of science replacing the icons of religion.

Even though I personally am an atheist and arguably a philosophical materialist, I still think religious modes of thinking can lead to very interesting mental places, even if they are in no way describing an existing external reality. To try and find these mental places without the trappings of religion, and to see legitimacy in them without needing to believe in their replication beyond the brain is an interesting task.

Some of your work in the Cosmonaut series is incredibly concise, sparse even. White space, black space, red space, there are literal and figurative references to space. What does this “space” represent?

I mostly think of my paintings as representations of internal mental states, so I don’t really see the black or the red background as outer space, but as part of the emotional state the painting as a whole is striving for.

The doves make an appearance across a couple of your series. Is there a continuity implied with this recurring element?

I love doves. They are one of the few species that really thrives in human created and controlled spaces. So their reoccurrence in my paintings is at least partly a function of that, they can stand in as non human life in human spaces without their appearance seeming unusual, and becoming the focus of the painting.

If your paintings were to be described by a song, what song would that be? Space Oddity by David Bowie is off limits…

Yeah, it wouldn’t be David Bowie. I listen to a lot of ambient/drone music when I am working, it helps me focus on the mood of the painting, and works as a sounding board (sorry for the pun) as I am trying to refine the work. If an element in a painting enhances the emotions the music is producing it is probably working, if it doesn’t, it probably needs to be removed.

Right now, the piece of music that is most working like this for me might be New Queens, by Phragments, which is very minimalist drone. If I was trying to find something a little less obscure, maybe something quiet and slightly melancholy from a composer like Nihl Frahm or Olafur Arnalds.

I sense space as a womb correlation, is that a conscious decision to use that as a metaphorical thread?

The cable/hose snaking away from the cosmonaut can be read an umbilical cord, and I’ve done at least a few painting where the cosmonaut is in something close to a fetal pose, so I can understand this reading, but for me it isn’t as close to the surface of my internal motivations as the religious reading.

What is your goal with your art?

I really want to trigger emotional or meditative states in the viewers, or at least a small percentage of them. Judging from emails we get this seems to be the case, so it is very satisfying that they can have that effect. I really just try to paint images that have that kind of effect on me, and then hope that there are some people out there whose internal life is similar enough to mine that they will feel the same.

What are you currently working on? Do you have any showings or events coming up in the near future?

I’m trying to get work produced for my next show at Jonathan Levine in NY, which is taking up all my time for the foreseeable future

This is the Third interview in the Realism series, and I gotta say that Jeremy Geddes is one of the most impressive and hardworking people who I’ve ever had the pleasure of corresponding with.

When I discovered Jeremy’s work it was a moment of straight up pure awesome, and not the casual slang use of awesome, but its original meaning which is to stand there gaping open mouthed and feeling totally overwhelmed. When I got his responses to the questions I had formulated I was really taken back. Reading through them I discovered that his execution of his thoughts is just as much a well refined process as his amazing artwork, he is eloquent and well measured in his opinions, and cuts through to some really profound and interesting ideas.

So without further ado here is Jeremy Geddes;

My first question to you is pretty straight forward: What is it that drove you to realism? And what keeps you doing what you do?

I can pretty easily trace a line between what I am doing now and what I was drawn to when I was ten, an inchoate collection of illustration and historical painting.

The relationship isn’t entirely direct, but the feelings and sensations that were created by looking at paintings then are the same ones I’m trying to capture now, albeit in a more sophisticated form. And that chase is still there; I’m still making the attempt and only partially succeeding. It’s what keeps me painting every day.

How do you go about developing your ideas for your pieces? Do you have a method for inspiration or is it more like “something pops into your head suddenly”?

It tends to be a process of refinement.

There will be an initial kernel of an idea or a feeling, but moulding that into something that can withstand translation into a full work takes a lot of time and thought.

I like to progress through a series of studies, living with each one for a while as I try to understand what is and isn’t working. At some point the image feels right, which leads on to the next revision and study and so on. Then down the track, if it passes the test, I feel justified launching into a full painting.

Is there someone else’s work that you can always return to for inspiration?

I look at different paintings for different aspects of my work. I look at Antonio Lopez Garcia for his beautiful mark making, not so much to emulate him, but to interrupt my pedantic inclinations and add some noise to the forms.

I love Wythe’s compositions and Hoppers treatment of the space figures occupy within their environments.

But mostly I listen to music. Music is often my way into a painting; during construction of a painting, it‘s the best way I’ve found to give clarity to the emotional throughline I’m trying to achieve.

What are your thoughts on conceptual art and its value? What about the conceptual art process?

Its value is measured in the same way as all other art, if it attracts an audience who are able to extract something useful from it, I think it can be described as having value. It holds no interest for me though. It’s completely removed from my concerns as a painter, and I’ve never really been able to extract much from it myself. Conceptual arts’ focus on process over engagement is alien to me.

It’s a very easy art form to attack and ridicule from the outside, but really, the utility of all art is questionable and when the foundations of your entire village is built on sand, it’s best not to go kicking in your neighbours wall.

What are your thoughts on the production art industry (film, T.V and games)? and the processes of having an army of artists working on a single project?

It’s giving a lot of artists a steady income and the value of that can’t be understated although the un-unionised nature of the industry and the threat of outsourcing seem to be leading to greater levels of exploitation, which is a worrying development.

As a concept, if it works for the artist, great, collaboration can be a powerful way to get work done. Historically I’m sure it’s more the norm than the solitary artist, I’m just personally not built for it.

When it comes to your own art making, how much time do you dedicate to the planning process? Is it a conscious effort or do you just go into autopilot?

The planning process is both conscious and a feat of ‘autopilot’. The realisation of what is and isn’t working has its own internal timescale, and I can’t force it beyond a certain point. I try to construct a system (via studies etc) that continually prods my brain with the problems that need to be addressed, but then you just have to wait until the answers are there. This process can easily take a year or two, rolling along in the background as I work on other pieces.

When was the Aha or Eureka moment when you realised that you had grasped the ability to paint realistically? Was it a massive breakthrough that made you want to jump up and down? Or was it a natural quiet progression?

I’ve had that moment a few times, a kind of internal hubristic rush, and later I always looked back and realised I was full of shit and completely deluding myself. Everything I’ve so far done feels completely bound by my technical limitations. I feel like I can break them, or at least push them back some and that’s one of the things that keeps me coming back each day.

What was the biggest hurdle you faced when learning art and especially making realistic art?

Deluding yourself that you are better than you are is certainly up there, but honestly, the biggest hurdle is money. It’s a struggle to be able to position yourself so you have the freedom to work as long as you need to on a piece and then destroy it because it’s not good enough. If you need the money to survive, to pay next month’s rent, the pressure is always there to work fast, and produce work that has a decent time to money ratio, which helps the painter eat, but isn’t necessarily the best work the painter can do, or the work that is best for her career.

What importance do you place on Realism in the world of art? Why do think it’s still one of the most popular styles?

Well, I’m drawn to realism, so obviously I will see it as fairly important. Is it popular within the ‘art world’? It would be nice if it was so, I haven’t really paid much attention. It was mildly sneered at back when I was at art school; perhaps that has changed. Certainly it’s popularity beyond the bubble of the ‘art world’ is easily explained, it has retained the hooks that can grab the attention of otherwise disinterested passersby, and gives them an avenue into the work that can then lead to a greater connection.

There are so many artists out there who want to do what you can do — because it’s awesome! For those aspiring to become realistic painters, what is the biggest mistake that you see them making? What do you think are the biggest wastes of time in the earlier stages?

For someone attempting realism, I’d say go in expecting to produce nothing of any merit for a while. Develop a critical eye, unflinchingly compare your work to those painters you admire, and then throw yours away and try again. I’d say it’s better to be too critical of your own work than not critical enough.

So in this sense ‘wasting time’ can be a loaded term. Making the same mistake again and again is probably a waste, but making a mistake and learning from it is a crucial step in learning and progression.

And concerning the professional level: What are most common mistakes that you catch yourself and other fellow pros making?

One mistake I often catch myself in is launching into a full sized painting before I have addressed and resolved all the potential problems in small scale studies. It means I can spend days or weeks in rework for an issue that could have been sorted out in hours if I had followed the correct procedure. Tampering down enthusiasm with pragmatism can be a tricky thing to hold onto sometimes, but it is almost always worth it.

Outside of that, I really don’t know. No-one else’s desired end point is the same as mine, and so I have no context to judge whether they are making the right decisions. If you are producing work you are happy with, and can keep a roof over your head doing it, I would say well done, it’s not an easy trick to pull off.

Finally, do you have any strong thoughts or opinions on the public’s perceptions of fine art? Particularly, can you comment on the audience’s common feeling of disconnectedness between a piece and the message behind it?

Last time I paid attention to it, the general public had little interest in the world of fine art, and rightly so. There’s still a huge love of art, but the art forms that the public flocks to (film, television, books and music) are generally placed outside of the sphere of ‘fine art’. The label ‘fine art’ is almost defined by its non-appeal to a broad audience. Many of its practitioners have spent the last one hundred years pulling apart the structures that gave their discipline its popularity. This is a profound and interesting direction for anyone already immersed in its culture and language but it eventually creates an impossible divide for outsiders to bridge.

So the disconnect between the intended meaning of a conceptual work and the meaning that ‘Joe Public’ will take from it is obviously huge, the work is most likely buried in decades of obscure theory that the public has no knowledge of or participation in.

To some extent, even when clear and unambiguous communication is the intent, all transmitted meaning is fractional and illusory. You can be reasonably sure of clear communication in a medium with a heavily established structure understood by both creator and viewer, for example, an action movie or a romantic comedy (but then you could argue whether much of merit or novelty is actually being said).

The moment you step away from a universally understood and shared structure, surety of accurate communication becomes shaky. This, to me, seems to be a problem with no solution. It’s inherent to the nature of the world we live in.